The history of Renaissance art has long been dominated by the names of male masters—Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael—while their female contemporaries were relegated to footnotes or forgotten entirely. Yet recent scholarship in feminist art history has begun to dismantle this patriarchal narrative, uncovering the remarkable contributions of women artists who flourished despite systemic barriers. These painters not only existed but produced work that rivaled their male counterparts in skill and innovation. Their exclusion from the canon speaks less to their talent than to the gendered biases that shaped art historical discourse for centuries.

One such figure is Sofonisba Anguissola, a Lombard noblewoman whose portraits captivated European courts. Born in 1532, Anguissola received rare artistic training from Bernardino Campi, defying conventions that deemed painting unsuitable for aristocratic women. Her 1559 Self-Portrait at the Easel subverted expectations by depicting herself not as a muse but as a creator—brush in hand, gaze steady. Unlike male artists who mythologized their genius, Anguissola’s work often explored domestic intimacy, as seen in The Chess Game, where her sisters engage in strategic play, their expressions alive with intelligence. Though praised by Vasari and appointed as court painter to Philip II of Spain, Anguissola’s legacy was later diminished through attributions to male artists like Titian.

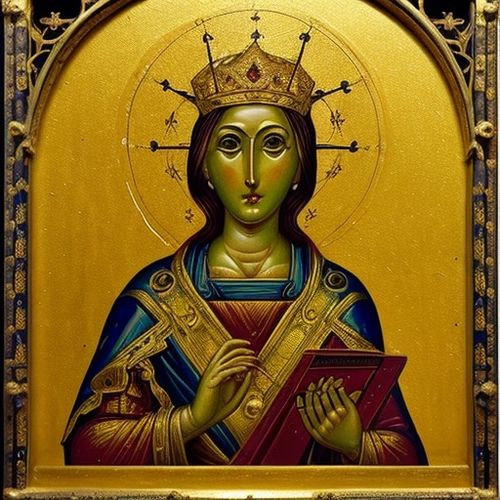

Equally groundbreaking was Lavinia Fontana of Bologna, the first professional female artist to run her own workshop. Fontana’s 1581 Portrait of a Noblewoman reveals her mastery of texture: the glint of pearls against black velvet, the delicate tracing of lace. By 1603, she broke another barrier by receiving a papal commission for an altarpiece—a domain strictly reserved for men. Her Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1595) reimagines the biblical heroine not as a seductress but as a composed aristocrat, her sword resting lightly on the severed head. Fontana’s success, however, came at a cost; she bore eleven children while maintaining her career, a duality scarcely acknowledged in contemporary accounts.

The Venetian Marietta Robusti, nicknamed "Tintoretta" after her famous father Jacopo Tintoretto, presents a more tragic narrative. Trained in her father’s bustling studio, Robusti excelled at portraiture, her 1585 Portrait of an Old Man and a Boy displaying psychological depth akin to Titian’s late works. Yet her potential was cut short by her death at thirty, possibly in childbirth—a common fate for Renaissance women. Posthumously, many of her paintings were absorbed into her father’s oeuvre, their true authorship obscured by the assumption that women couldn’t achieve such technical prowess.

Why did these artists vanish from mainstream art history? The answer lies in Renaissance societal structures. Guilds barred women from apprenticeships, forcing female artists to rely on familial connections. Treatises like Alberti’s On Painting framed art as a masculine pursuit, while Vasari’s Lives of the Artists—the era’s definitive text—featured only four women among hundreds of men. Even when recognized in their time, female painters faced posthumous erasure through misattribution or dismissal as "exceptions." The 20th-century art market compounded this by valuing male signatures, leaving many works by women languishing in museum storerooms.

Contemporary feminist art historians employ innovative methods to reclaim these narratives. Technical analysis like X-ray imaging has revealed pentimenti (artist’s revisions) proving female authorship, while archival research uncovers contracts and correspondence documenting women’s professional activities. Exhibitions such as Making Her Mark (2023) at the Baltimore Museum of Art have reintroduced figures like Plautilla Nelli, a Florentine nun whose monumental Last Supper (1568) predates Vasari’s by two decades. Such efforts challenge the myth of the solitary male genius, revealing instead a collaborative, gendered art world where women negotiated creative expression within strict confines.

The implications extend beyond art history. Recovering these painters reshapes our understanding of Renaissance culture itself—not as a monolithic "rebirth" led by men, but as a complex tapestry woven by diverse hands. Their rediscovery also prompts uncomfortable questions: How many masterpieces hang in museums under false attributions? What current biases still dictate whose art we value? As scholar Sheila Barker notes, "The canon isn’t an immutable truth but a construct we continually reassess." In that reassessment, the brushes once held by Sofonisba, Lavinia, and Marietta finally return to view, demanding their rightful place in the frame.

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025